by Gerd Heber, Executive Director, The HDF Group

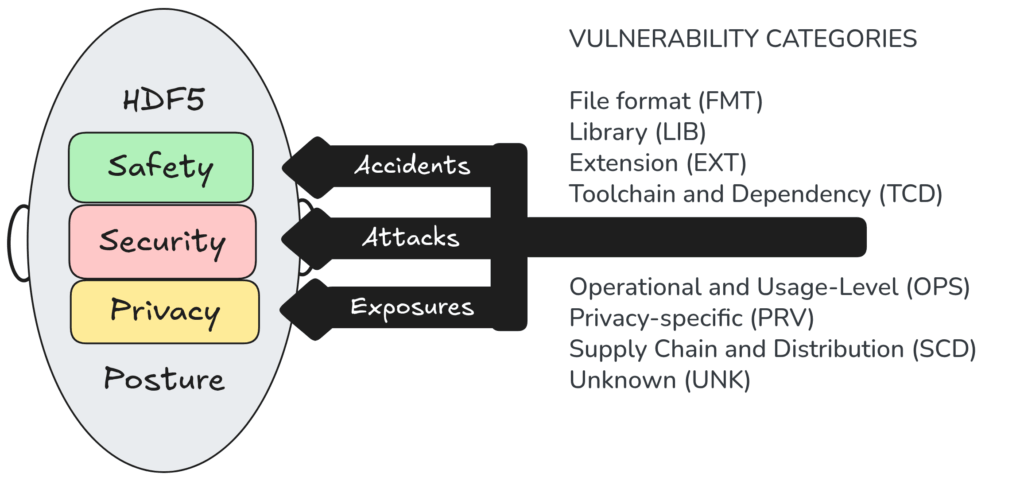

TL;DR Use three tags when you talk about risk in the HDF5 ecosystem—impact (Safety / Security / Privacy), incident lens (Accident / Attack / Exposure), and location (FMT / LIB / EXT / TCD / OPS / PRV / SCD / UNK).

- This keeps discussions precise: we can separate what happened from where the weakness lives.

- It improves triage: the right mitigation for a file-format ambiguity (FMT) is different than for a supply-chain weakness (SCD) or an operational misconfiguration (OPS).

- Overlaps are expected—tag multiple categories when needed. The goal is coordination, not perfect taxonomy.

Open-source data infrastructure has become part of our critical infrastructure. HDF5 sits in the middle of many scientific and industrial workflows, so failures can have wide blast radii—from silent data corruption, to denial-of-service in shared environments, to unintended disclosure of sensitive metadata.

In the NSF Safe-OSE framing, “risk” spans safety, security, and privacy (not security alone) and includes both technical and socio‑technical vulnerabilities. In our HDF5 SHINES (Securing HDF5 for Industry, and National Security, Engineering, and Science) effort, we’re adopting that posture with a very practical goal: a shared vocabulary that helps the community spot patterns, assign ownership, and prioritize engineering and operational work.

Why we keep saying “Safety, Security, and Privacy” (SSP)

In many contexts, “security” becomes shorthand for everything bad that can happen. For HDF5, that shortcut gets in the way of effective mitigation because it blurs three different kinds of harm:

- Accidents: unintentional failures (corrupted files, brittle integrations, unexpected edge cases).

- Attacks: intentional adversarial actions (malicious files, compromised plugins, hostile environments).

- Exposures: unintended disclosure of sensitive information (metadata leakage, re-identification risk, operational leakage).

By naming all three, we can be explicit about intent and impact—without arguing about whether something “counts” as a security issue.

Safety vs. security vs. privacy in HDF5

These are pragmatic definitions meant to help engineers and users communicate clearly. They are not meant to replace formal standards; they are meant to make day-to-day triage easier.

Safety: preventing harm from accidents and failures

Safety issues are failures that cause harm without requiring an adversary. In HDF5, “harm” often looks like:

- Wrong scientific conclusions due to corrupted or misinterpreted data.

- Crashes or hangs in critical pipelines.

- Resource exhaustion that takes down shared infrastructure.

Typical HDF5-flavored safety examples:

- A corrupted HDF5 file (truncated transfer, disk error) causes a reader to crash or hang instead of failing cleanly.

- A valid but extreme file layout triggers pathological CPU/memory behavior (e.g., runaway recursion or huge metadata traversal).

- A filter or plugin misbehaves and silently produces incorrect output.

Safety is where robustness, correctness, and resilience to weird (but non-adversarial) inputs live.

Security: resisting attacks

Security issues assume intent: someone crafts inputs or manipulates the environment to produce an outcome they want (code execution, data tampering, denial-of-service, privilege escalation).

Typical HDF5-flavored security examples:

- A crafted HDF5 file exploits a parsing weakness to crash an application or trigger arbitrary code execution.

- A malicious or compromised VOL/VFD/filter plugin runs with the privileges of the host process and can do much more than “I/O.”

- A compromised distribution channel or build pipeline results in trojanized binaries or plugins.

Privacy: controlling unintended disclosure

Privacy issues are about sensitive information being exposed—whether through design gaps, metadata leakage, misuse, or side effects. Privacy is not only about encryption; it’s also about what leaks through structure, names, defaults, logs, and operational practice.

Typical HDF5-flavored privacy examples:

- Sensitive identifiers embedded in group names, attributes, or link metadata are shared “in plain sight.”

- A workflow encrypts only the raw data while leaving identifying metadata readable and linkable.

- Extensions leak sensitive state through side effects, logs, or metadata manipulation.

The “SSP Trident” mental model

To keep conversations grounded, we use a simple mental model: separate (1) the kind of incident we care about from (2) where the weakness lives.

What the figure conveys (in words):

- On the left is the HDF5 posture, composed of Safety, Security, and Privacy measures.

- The trident’s prongs are Accidents, Attacks, and Exposures—a reminder that the ecosystem must withstand more than adversarial exploitation.

- On the right are vulnerability categories that help us locate where a weakness lives: format, library, extensions, toolchain/deps, operations, privacy-specific mechanisms, supply chain, and unknowns.

This separation helps answer two different questions:

- What kind of incident are we worried about? (accident vs. attack vs. exposure)

- Where does the weakness live? (format vs. library vs. plugin vs. toolchain vs. operations vs. supply chain, etc.)

The vulnerability categories we use (and why)

In our HDF5 SHINES work, we group issues into seven categories, plus UNK for things we haven’t classified yet. These categories are not disjoint; real incidents often span multiple categories.

FMT: File format vulnerabilities

Weaknesses in the serialized representation and the parsing/validation implications of the spec.

Typical mitigations: clarify spec edge cases, add canonicalization guidance, improve validation and test vectors.

LIB: Library vulnerabilities

Issues in the core HDF5 implementation (parsing, memory management, concurrency, API behavior).

Typical mitigations: fuzzing, hardening, memory-safety strategies, safer defaults, better error handling.

EXT: Extension vulnerabilities

Risks in VOL/VFD/filter plugins and other extension points—powerful, but often at trust boundaries.

Typical mitigations: signing/verification, sandboxing, allowlists, review + CI for extension interfaces.

TCD: Toolchain and dependency vulnerabilities

Risks from build systems, packaging, and transitive dependencies (e.g., compression backends).

Typical mitigations: SBOMs, CVE scanning, pinned dependencies, reproducible builds, verified build artifacts.

OPS: Operational and usage-level vulnerabilities

Misconfigurations, unsafe practices, or missing controls in real deployments.

Typical mitigations: hardened defaults, deployment guidance, secure configuration options, logging hygiene.

PRV: Privacy-specific vulnerabilities

Design/workflow failures that create sensitive leakage even without a classic “bug.”

Typical mitigations: metadata minimization, redaction guidance, privacy-by-design defaults, documentation and templates.

SCD: Supply chain and distribution vulnerabilities

Risks from how artifacts are produced/distributed (unsigned builds, compromised repos, typosquatting).

Typical mitigations: signed releases, provenance attestations, trusted distribution channels, transparency and verification.

UNK: Unknown

A practical bucket for issues where we don’t yet understand impact or root cause well enough to classify.

Typical mitigations: reproduce, minimize, and gather evidence until classification is responsibleWhy this categorization is helpful (even though it overlaps)

Overlaps are a feature, not a bug. This taxonomy helps us:

- Avoid one-size-fits-all thinking. “Security bug” is too broad; a format-level ambiguity (FMT) doesn’t get fixed the same way as a supply-chain weakness (SCD) or an operational misconfiguration (OPS).

- Make cross-layer incident chains visible. It becomes normal to say: “This started as a file-level trigger (FMT), but exploitability depended on a library weakness (LIB), a plugin-loading policy (EXT/OPS), and distribution trust (SCD).”

- Assign ownership and prioritize work. Different categories map to different owners and timelines (spec/tooling vs. core library vs. packaging/distribution vs. deployment).

- Improve reporting quality. When someone reports a problem, it’s immediately useful to know the incident lens (accident/attack/exposure) and the likely categories implicated.

One last note: HDF5 “data” can be part of the attack surface

A subtle but important theme is that the file format’s openness and the ecosystem’s ubiquity can turn data itself into a delivery vehicle.

HDF5 is integral to ML and data-at-scale workflows where validating provenance and detecting malicious alteration can be hard. That’s why our vocabulary explicitly includes supply chain and privacy alongside classic library vulnerabilities..

Closing: using the vocabulary as a community tool

The goal of a shared vocabulary isn’t to police language—it’s to make collaboration easier.

If you’re filing an issue, reviewing a PR, or documenting a best practice, try tagging your discussion with:

- Impact axis: Safety / Security / Privacy

- Incident lens: Accident / Attack / Exposure

- Category tags: FMT / LIB / EXT / TCD / OPS / PRV / SCD / UNK

That simple discipline makes it easier to see patterns, avoid gaps, and build an HDF5 ecosystem that’s not just secure, but also safer and more privacy-aware by default.

Let it shine!

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Federal Award No. 2534078. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.